LOS ANGELES ARTIST JOHN KNUTH PAINTS WITH FLYSPECK. THAT IS NOT A TYPO; HE USES THE DIGESTIVE PROCESS OF INSECTS TO CREATE HIGH-END, TRANSCENDENT MODERN ART THAT SELLS ALL OVER THE WORLD. THIS SUMMER, KNUTH AND HALF A MILLION OF HIS WINGED FRIENDS HAVE BROUGHT AN INTERACTIVE NEW SHOW TO DENVER. LET THE BUZZ BEGIN.

WORDS: CHARLIE KEATON | IMAGES COURTESY OF JOHN KNUTH AND DAVID B. SMITH GALLERY

First things first: Find yourself a reputable biological supply company and place an order for one million maggots. Delivery will take a few days—it’s probably a good idea to spring for tracking and insurance on this one—and while you’re waiting, get to work building contraptions to house these maggots once they become flies. You’ll need straight wood (poplar is good) and some tropical hardwood fiberboard called luan, used in everything from boats to dollhouses. Make sure to have plenty of nails, glue, primer, paint, canvas, and sugar water on hand, plus all the corresponding tools for each. The contraptions take about three days, start to finish. Once the maggots arrive, they’ll need five days to pupate. Then it’s time to make something uniquely, paradoxically beautiful.

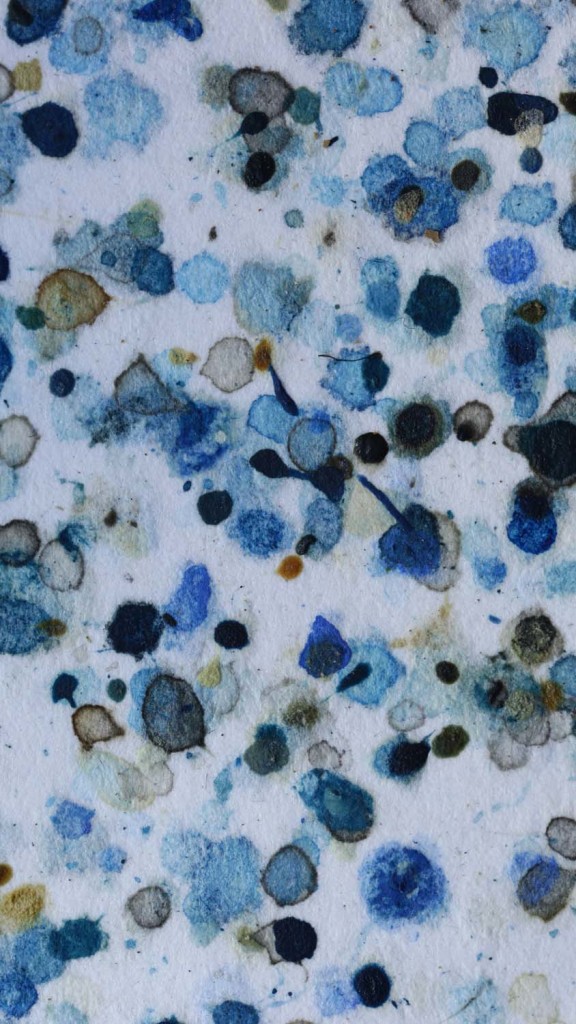

John Knuth paints with flies. There’s no other way to say it, no euphemistic expression to conceal the hard truth about the process he endures in the name of artistic creation. Flies are filthy creatures. But the paintings they produce by his hand are other-worldly.

John Knuth paints with flies. There’s no other way to say it, no euphemistic expression to conceal the hard truth about the process he endures in the name of artistic creation. Flies are filthy creatures. But the paintings they produce by his hand are other-worldly.

Whitney Carter, Director at David B. Smith gallery in LoDo, has known Knuth for years. “A lot of time when you’re describing it, people can’t get past the repulsion,” she said. “But it’s an interesting layer to the work that you’re forced to get past your ideas about what flies are and then to see this beautiful object that they produce.”

Whitney Carter, Director at David B. Smith gallery in LoDo, has known Knuth for years. “A lot of time when you’re describing it, people can’t get past the repulsion,” she said. “But it’s an interesting layer to the work that you’re forced to get past your ideas about what flies are and then to see this beautiful object that they produce.”

So how, exactly, do flies paint? And why has Knuth gone to so much trouble when more traditional methods seem to work just fine? The biological process itself is fairly simple—a clever utilization of natural bodily functions—but the preparation, and the larger ideas behind his work, are much more complex.

So how, exactly, do flies paint? And why has Knuth gone to so much trouble when more traditional methods seem to work just fine? The biological process itself is fairly simple—a clever utilization of natural bodily functions—but the preparation, and the larger ideas behind his work, are much more complex.

Start with what Knuth calls his “contraptions,” built by hand in his Los Angeles studio. Each one measures 5 feet by 3 feet. His flies eventually live, eat, and paint here. Lining the walls of each contraption are canvases, standing face-to-face after being stretched and primed and covered in a monochromatic base. The flies are introduced to their new home and fed a mixture of water, sugar, and a heavily pigmented acrylic paint.

Start with what Knuth calls his “contraptions,” built by hand in his Los Angeles studio. Each one measures 5 feet by 3 feet. His flies eventually live, eat, and paint here. Lining the walls of each contraption are canvases, standing face-to-face after being stretched and primed and covered in a monochromatic base. The flies are introduced to their new home and fed a mixture of water, sugar, and a heavily pigmented acrylic paint.

This is where biology takes over, because flies don’t have a moving mouthpiece to chew and bite. Instead they have a proboscis, a straw-like piece of anatomy that allows them to regurgitate a digestive enzyme onto whatever they’re eating. That enzyme breaks down the food, and the resulting juice gets sucked back in. In other words, flies are in a more-or-less constant state of regurgitation, spreading the contents of their stomach onto every surface they encounter.

This is where biology takes over, because flies don’t have a moving mouthpiece to chew and bite. Instead they have a proboscis, a straw-like piece of anatomy that allows them to regurgitate a digestive enzyme onto whatever they’re eating. That enzyme breaks down the food, and the resulting juice gets sucked back in. In other words, flies are in a more-or-less constant state of regurgitation, spreading the contents of their stomach onto every surface they encounter.

Knuth first was interested in how this digestive process enabled flies to spread disease. Over time, he began to see that their behavior corresponded with certain aspects of human life in major metropolitan cities. He created his first flyspeck paintings by feeding flies typical American fast food. The results were interesting but drab—lots of brown spots atop more brown spots. Then, an epiphany: “I realized that I could control the pigment and the color, and I became interested in creating something transcendent with the baseness of the flies,” Knuth said. “There’s nothing worse than a fly, and I liked the idea that you could really create something magical and delicate from something so nasty.”

Knuth first was interested in how this digestive process enabled flies to spread disease. Over time, he began to see that their behavior corresponded with certain aspects of human life in major metropolitan cities. He created his first flyspeck paintings by feeding flies typical American fast food. The results were interesting but drab—lots of brown spots atop more brown spots. Then, an epiphany: “I realized that I could control the pigment and the color, and I became interested in creating something transcendent with the baseness of the flies,” Knuth said. “There’s nothing worse than a fly, and I liked the idea that you could really create something magical and delicate from something so nasty.”

The resulting work has turned heads, and not just because of the unusual workflow. Featured in major exhibitions from Chicago to Milan, Knuth’s paintings are genuinely captivating. The price tags start at $3,000. And the way he goes about creating it never fails to start a conversation. “His paintings are gorgeous and stunning to look at, and it’s so interesting to learn about the process,” said Owner/ Director David Smith. “His works cross various lines: minimalism, performance, a little bit of conceptual art. And it results in these stunning paintings.”Smith ought to know. He is hosting Knuth, along with 500,000 winged collaborators, at his David B. Smith gallery until July 3. The exhibition, “Nothing Without Providence,” is named for the Colorado state motto, and has offered unprecedented access to not just the finished product, but to the artistic process itself. Knuth arrived in Denver weeks before opening night and used that time to prepare his contraptions, flies, and canvases for the very public exhibition.

The resulting work has turned heads, and not just because of the unusual workflow. Featured in major exhibitions from Chicago to Milan, Knuth’s paintings are genuinely captivating. The price tags start at $3,000. And the way he goes about creating it never fails to start a conversation. “His paintings are gorgeous and stunning to look at, and it’s so interesting to learn about the process,” said Owner/ Director David Smith. “His works cross various lines: minimalism, performance, a little bit of conceptual art. And it results in these stunning paintings.”Smith ought to know. He is hosting Knuth, along with 500,000 winged collaborators, at his David B. Smith gallery until July 3. The exhibition, “Nothing Without Providence,” is named for the Colorado state motto, and has offered unprecedented access to not just the finished product, but to the artistic process itself. Knuth arrived in Denver weeks before opening night and used that time to prepare his contraptions, flies, and canvases for the very public exhibition.

For the first two weeks, when guests walked in the gallery’s front door, they were greeted by an internationally known artist creating original works via flyspeck. “John basically set up his studio in the gallery,” said Carter. “For people to come in and meet the artist, to see him making the paintings, and to watch them happen in stages, is pretty unique and special.” On June 13, the paintings were finished and installed; they remain on display until July 3.

For the first two weeks, when guests walked in the gallery’s front door, they were greeted by an internationally known artist creating original works via flyspeck. “John basically set up his studio in the gallery,” said Carter. “For people to come in and meet the artist, to see him making the paintings, and to watch them happen in stages, is pretty unique and special.” On June 13, the paintings were finished and installed; they remain on display until July 3.

For his part, Knuth is excited to be spending the summer in Colorado. Despite his status as an ascending talent in the Los Angeles art world, the native Minnesotan has never lost his connection with nature. Much of his work is inspired by the natural world, and he makes a point to seek out pockets of urban adventure amidst the city-based existence of southern California. “I think I’m the only guy in L.A. who owns a canoe,” he said.

For his part, Knuth is excited to be spending the summer in Colorado. Despite his status as an ascending talent in the Los Angeles art world, the native Minnesotan has never lost his connection with nature. Much of his work is inspired by the natural world, and he makes a point to seek out pockets of urban adventure amidst the city-based existence of southern California. “I think I’m the only guy in L.A. who owns a canoe,” he said.

The canoe didn’t make the trip this time, but what Knuth brought to Denver instead—contraptions, flies, and the ability to create breathtaking work in real time on the floor of a major gallery—is bound to get noticed. He paints like no one else. But does he even consider himself a painter? “I always think of myself as being a sculptor,” said Knuth. “As a painter, you’re moving paint around on a canvas. With this I’m physically working with something that has duration, that has three-dimensional space, and the contraptions that hold the flies are sculptures. I’m excited that with this show, people got to see that it really is like a material manipulation practice.”

The canoe didn’t make the trip this time, but what Knuth brought to Denver instead—contraptions, flies, and the ability to create breathtaking work in real time on the floor of a major gallery—is bound to get noticed. He paints like no one else. But does he even consider himself a painter? “I always think of myself as being a sculptor,” said Knuth. “As a painter, you’re moving paint around on a canvas. With this I’m physically working with something that has duration, that has three-dimensional space, and the contraptions that hold the flies are sculptures. I’m excited that with this show, people got to see that it really is like a material manipulation practice.”

Whatever he calls it, you won’t be able to take your eyes off it.