Words: Melissa Belongea / Images: Trevor Brown | Andrew Clark Studio

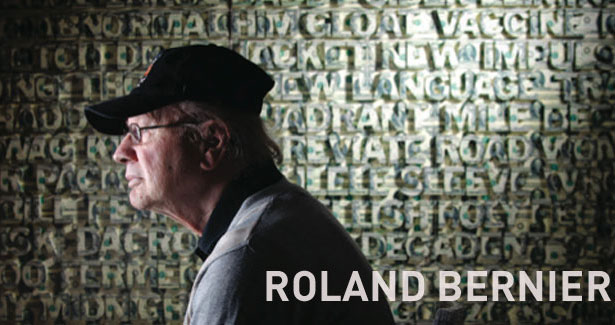

Roland Bernier has a way with words. Not in the traditional sense of writing and composition, but by using words to convey his art. Bernier, who knew he wanted to be an artist from a very young age, has been making and studying art for over 50 years. He has been using words as his medium for 45 of those.

While meaning may be nearly untraceable in Bernier’s work, certainly he expresses references that are both verbal and visual. Recently, Bernier had his own hands molded for use in a series of pieces where the pair of hands sit open to an associated word. In each of these pieces, the hands are covered in a way that references the letters being held. There is no meaning beyond this simple relationship, but it is enough to make the viewer think about what the artist is doing. Bernier says he intentionally uses cliches in his work, but aims to re-invent them. This is achieved by taking words that normally have a strong association, where the viewer might be looking around for other clues as to why that specific word was chosen. However, the viewer will find no greater rhyme or reason, other than perhaps Bernier simply likes the way the word looks aesthetically or for the word’s potential to be reinvented.

Considering all this time, Bernier still finds ways to keep his work fresh and relevant. It is his intention and his result. He carries specific and significant influences from various, related periods in art history (Impressionism, Dadaism, Contemporary Art and Postmodernism). For someone who has passed through so many durations of art movement, where it is easy to dwell and stagnate in the past, Bernier’s work is the opposite, it remains a contemporary reflection of an artist with an enduring and timeless perspective of art.

Although Bernier assigns his dedication to the use of words, most of the time the words he chooses reflect no meaning. That is, many of his compositions are simply letters situated next to one another. The artist says he does not use words to make sense and this is a specific technique meant to break down barriers of conventional definitions of art (art created with inflated meaning as well as using only traditional mediums such as paint and sculpture). Bernier sites the Impressionists as one of his major influences, when the practice of painting was turned upside down by a group of artists who interpreted a different use of the medium. Bobbie Walker of Walker Fine Art, who represents the artist here in Denver, draws a connection to Dadaism in Bernier’s work as well. “Dadaists rejected the prevailing standards of logic in art, embracing chaos and irrationality. Initially Roland felt he had to break down the barriers of making sense by just listing words taken at random from the dictionary and putting them on canvas and board. The idea of taking the word out of context opened a new visual world for him,” says Walker.

In another recent piece, Bernier took old beer cans and arranged them to spell the word, “BEER CANS” for an exhibition titled, ‘Words Themselves’ at Spark Gallery in the Santa Fe Arts District. It’s a straightforward aesthetic approach that brings out the inevitable question, ‘what is art?’ Demonstrated in this piece, Walker explains Bernier’s context in contemporary art history, “Leading into the Contemporary era, artists began making art for arts sake by taking mundane, ordinary objects and abstracting them conceptually, by taking them out of their everyday context and presenting it as “art.” This approach to creating art took a strong hold in New York in the 1960s, [where Bernier lived from 1966-1971] placing Roland Bernier directly in the heart of pure formalist aesthetics.”

In addition to art-making, Bernier has also taught art extensively. After completing a master’s degree from the University of Southern California, Bernier began his teaching career at the University of Houston in 1961. The artist held subsequent positions at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, Sirovich Center (NYC) and most recently the Park Avenue Recreation Center in Denver. He moved to Denver with his wife in 1973.

Throughout Bernier’s varied, rooted and historical artistic career, he brings to the art world a reminder about the removal of preconceptions. Stringing together influences dating back to the mid-1800s to make this point, Bernier’s work and its longevity says a lot (even if the words he uses do not). Walker articulates his classic style, “Even the older bodies of [Bernier’s] work do not look dated, the art feels just as fresh today as it did then. His aesthetic is so tight that it is difficult to identify which of his work is brand new and what was created twenty, even thirty years prior.” For his next exhibition the artist was asked to provide his signature work. In true and evolving form, Bernier will be presenting us with a literal twist on this theme.