Whatever the message, volume, or venue, the prints we hang on our walls serve as little amplifiers for our thoughts. Whether a gig poster or a giclée, the poster art medium is recognized as a legitimate component of contemporary decorative expression. But how did this come to be? How did information evolve into an art form? And what does it mean today? To understand the modern poster’s function in contemporary design, it’s necessary to unearth a deeper understanding of the nature of visual—and aural—communication.

WORDS: CORY PHARE | IMAGE: CRYSTAL ALLEN

A fuzzed-out Fender guitar, or a wash of ambient texture. A roar, or a hush. An exclamation point, or parentheses. Contrasting, or contiguous.

A fuzzed-out Fender guitar, or a wash of ambient texture. A roar, or a hush. An exclamation point, or parentheses. Contrasting, or contiguous.

This can be what it’s like to look at poster art in whatever form. The amount of symbols and messages bombarding us daily is overwhelming, so it’s easy to overlook the semiotics of the homemade flier on a telephone pole advertising a Wednesday night show at the local dive. Yet that flier is an age-old part of posted visual communication, whose family tree stretches back centuries—and forward, into our living rooms today.

“Design is the most democratic of the arts; it’s something individuals can have some relationship with,” said Darrin Alfred, Associate Curator of Architecture, Design, and Graphics at the Denver Art Museum. “People today have a significant appreciation of design.” This appreciation underlies our décor decisions, whether it’s something purchased in a retail store or created with our own hands. Or as Denver-based Ink Lounge Creative Studio owners Stu and Nicky Alden put it, telling our own authentic story. “It’s a reflection—a personal connection,” said Nicky. “They’re meant to be enjoyed, rather than acted upon.”

The history of the poster is rooted in advertising, printing innovation, and mass distribution. Through technological advances in each of these areas, the poster became an ascendant global confluence of art and commerce. Each culture and time period left an impression as distinct as an etched plate applying oil-based ink to a flat surface— the process known as lithography.

Styles of posters vary greatly based on their ages and places of origin, according to Lisa Tyler of Gallerie Rouge, a vintage poster retailer in Cherry Creek. Posted bills have existed for centuries as proclamations, solicitations, or provocations, but it wasn’t until the 1870s that color-printing techniques allowed production on a widespread level. This chromolithography ushered in mass production of advertising bills, which spread through Europe in the 1890s and saw the rise of notable French printmakers such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Jules Chéret. Stateside, Americans were filled with wonder by the fantastical images of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey’s Circus advertisements. With easy access to color and playful use of typography, the aesthetic marriage of poster art and commerce was well in place by the turn of the century.

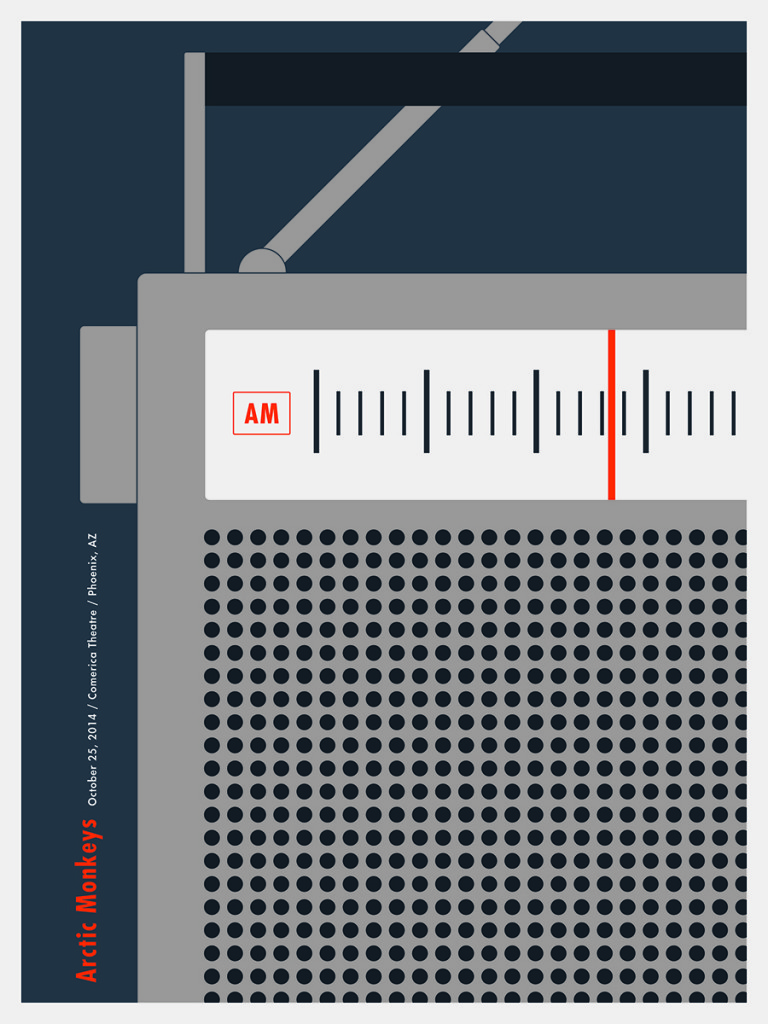

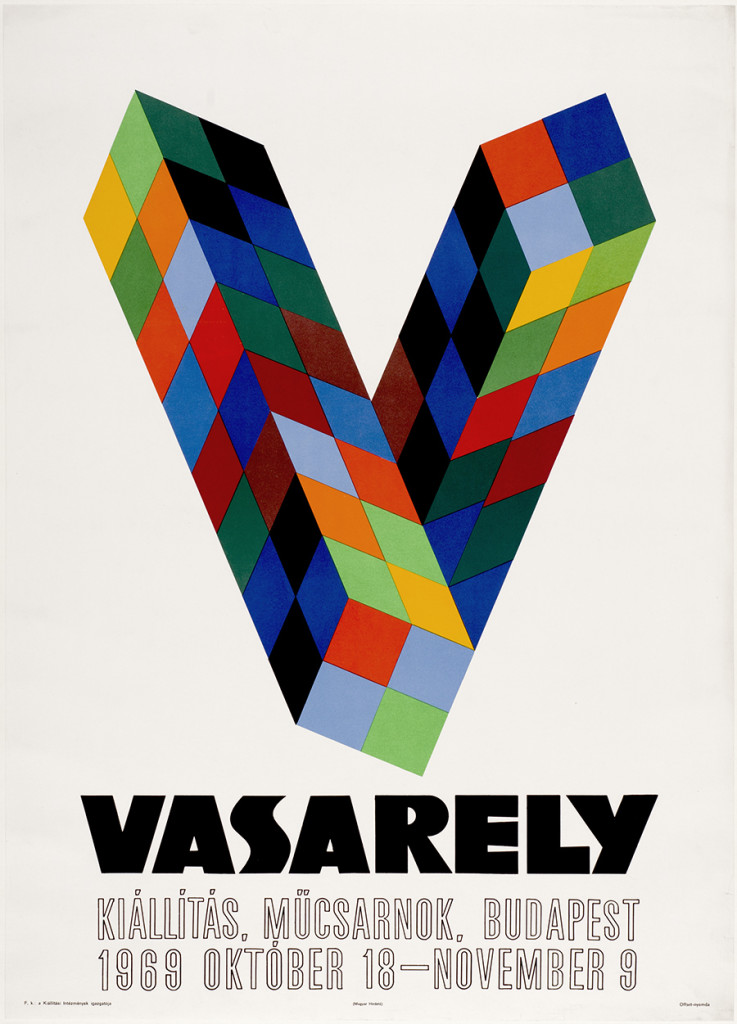

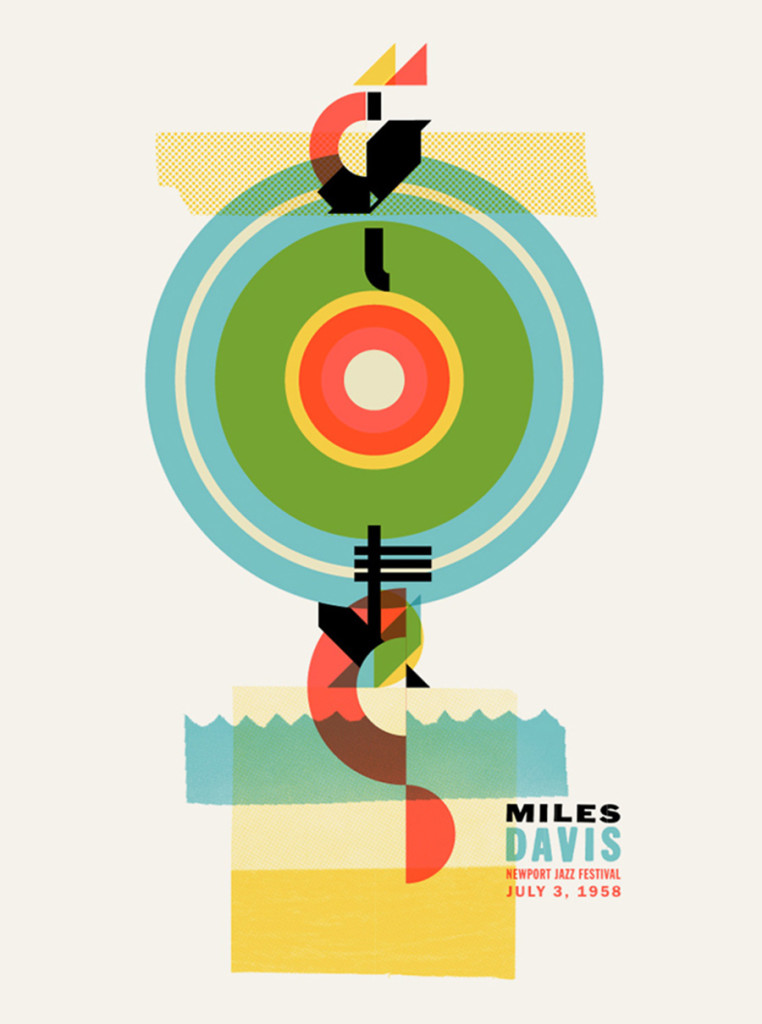

The poster’s Art Nouveau beginnings gave way to the Art Deco style prevalent through World War II, used by propagandists and profiteers alike. These print progenitors ushered in the advent of the medium’s relationship with Modernism that can still be seen today in the smooth simplicity of Jason Munn’s work. Saul Bass taught us that design was thinking made visual, and that work was serious play in his film posters. Charley Harper said, “In a world of chaos, the picture is one small rectangle in which the artist can create an ordered universe.” And what a unique universe it was—as either celebration of or reaction to industrial progress. With heavy angles and simple representation of the subject, these prints are extremely popular with mid-century modern fans today, according to Tyler. She also points out one specifically intriguing outlier during this time: “This may seem curious, but in the 1950s to the present, Poland has produced an abundance of edgy, attractive posters. It is very avant-garde.”

Flash forward—or back—to the late 1960s: There’s something happening in the Bay Area art-poster world, and it is clear in retrospect as an explosion of creative expression. At the center was the “Big Five” collective of Alton Kelley, Victor Moscoso, Rick Griffin, Wes Wilson, and Stanley Mouse, who designed posters for Frank Zappa, Jefferson Airplane, Sergeant Pepper’sera Beatles, and even Andy Warhol (on the road with The Velvet Underground and Nico). This offset lithography was the revolutionary spark that put America uniquely on the printed landscape and what led Darrin Alfred to develop The Psychedelic Experience: Rock Posters from the San Francisco Bay Area, 1965-71 exhibit at the Denver Art Museum in 2009. With fertile musical soil, the gig poster exploded as innovative agitprop for the Kandy-Kolored zeitgeist.

Unlike lithographic printing, screen printing is a process that uses a mesh-based stencil or screen to apply ink to planar and nonplanar surfaces alike. Production stretches back as far as 960 A.D. to the Chinese Song Dynasty and is still fundamentally intact today—remaining an intimate, artisanal undertaking, which puts the creator in direct contact with each piece created. As ink is wiped from the stencil by human hand, slight imperfections emerge on each unique print. “There’s somebody involved in every step of the process; there’s a tangible difference that matters,” said Stu Alden. “We see the imperfections as charming and tell everyone to ‘Embrace the Charm.’” This manifesto dons the wall of the Ink Lounge in the form of pictures of community members displaying their creations.

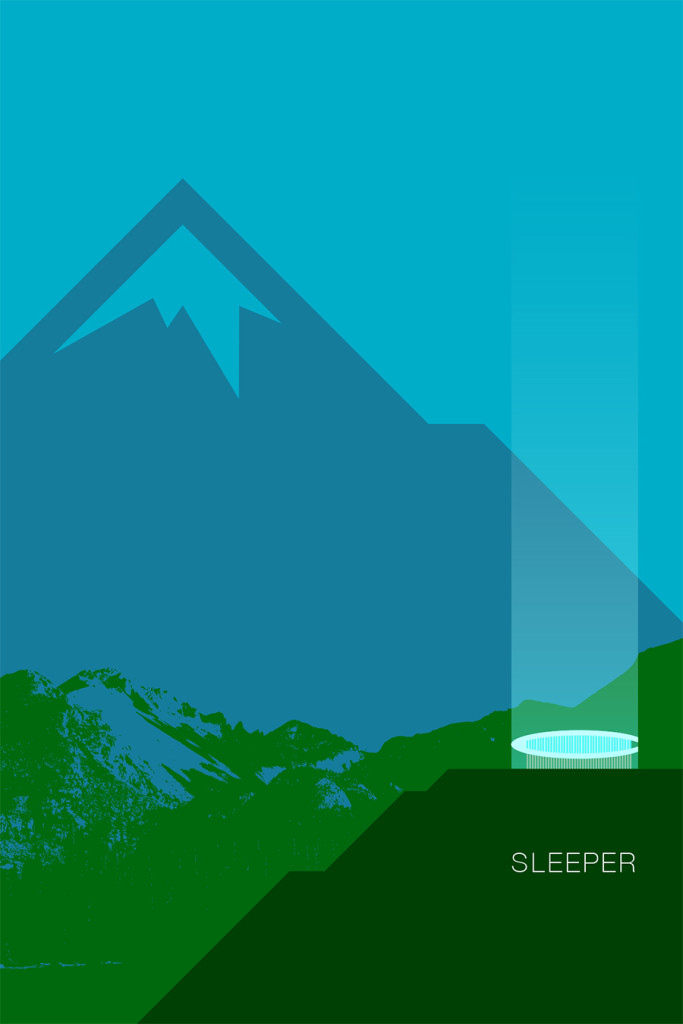

One of these creators who can call this space home is local artist John Vogl, who runs a design, illustration, and art direction studio known as The Bungaloo. Having created limited edition posters for bands as diverse as Mogwai, Mumford & Sons, and Mastodon, Vogl also designs art prints not tied to specific musical acts. “It’s really gratifying to have one come up organically, someone requesting a piece in a specific style,” he said. “It becomes something with a unique voice that’s more about an aesthetic.”

That unique aesthetic fuels incorporation of the poster into modern interiors. “It runs across the design realm,” Alfred said. “People are more in-tune with construction and design in general, across commercial and beyond.” It’s why, as everyone we interviewed pointed out, the poster is an accessible opportunity to make a statement, be it overt or subtle. From democracy of digitization to craft of the handmade, the fundamental human element of communication is why the poster continues to reside as a contemporary design component at the corner of art and design. It’s why we look fondly at a gig poster and are immediately transported back to a memory, with the sheen only reflection can bring. It’s the same reason we hang a child’s drawing on our refrigerators or a flier to a telephone pole, looking simultaneously backward and forward.

Inspirational, conversational, or confrontational, posters can be catalytic—a call to action and a reaction. Close your eyes. Can you hear the roar of a crowd or the hush of reverence? Can you feel the energy of the message from the amplifier on the wall? In retrospect, it was never a poster to begin with—it was a window.