Art and design aficionados already know the Denver Art Museum offers some of the finest Modernist viewing around. Now Gwen Chanzit, the Curator of Modern Art who brought us Figure to Field: Mark Rothko in the 1940s, recently unveiled another show-stopping exhibition at the DAM just in time for summer.

WORDS: KIMBERLY MACARTHUR GRAHAM

WORDS: KIMBERLY MACARTHUR GRAHAM

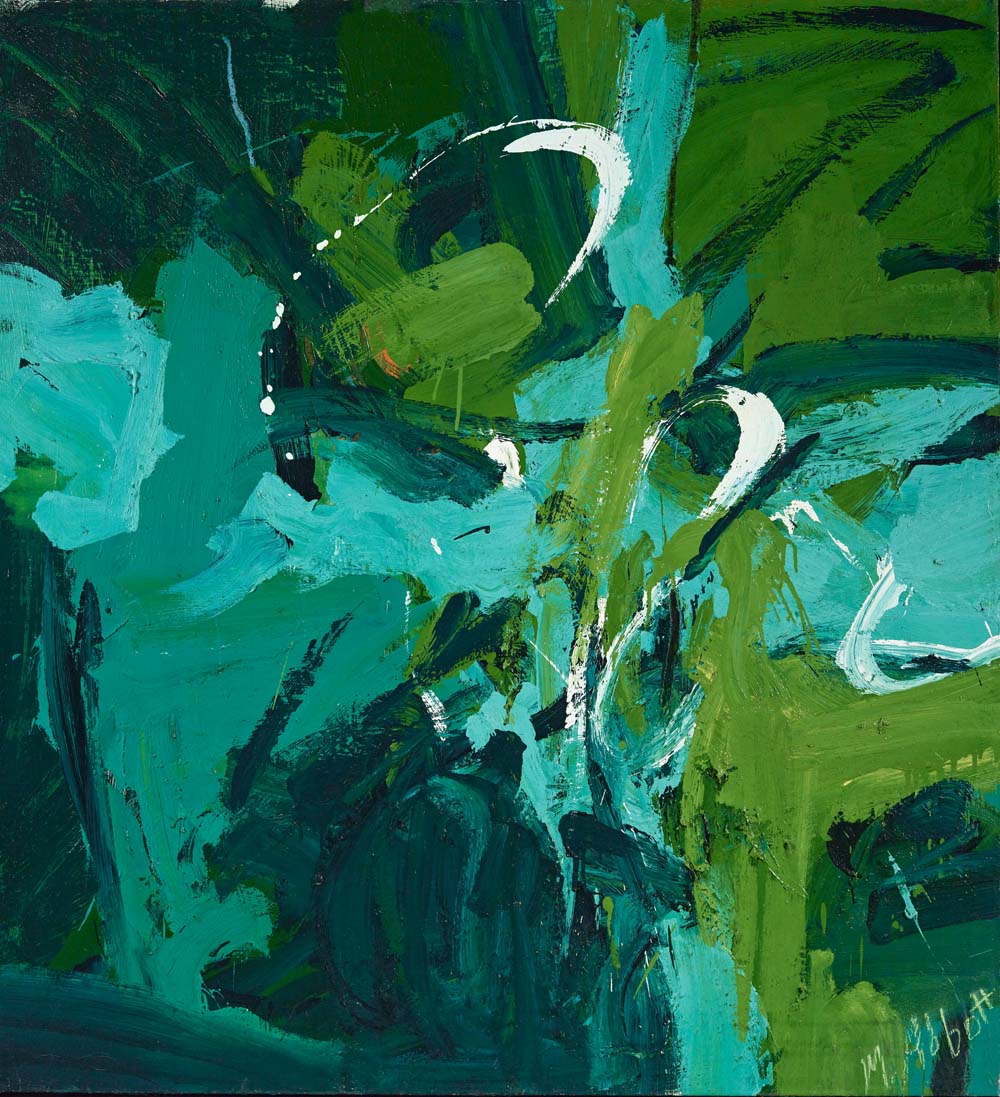

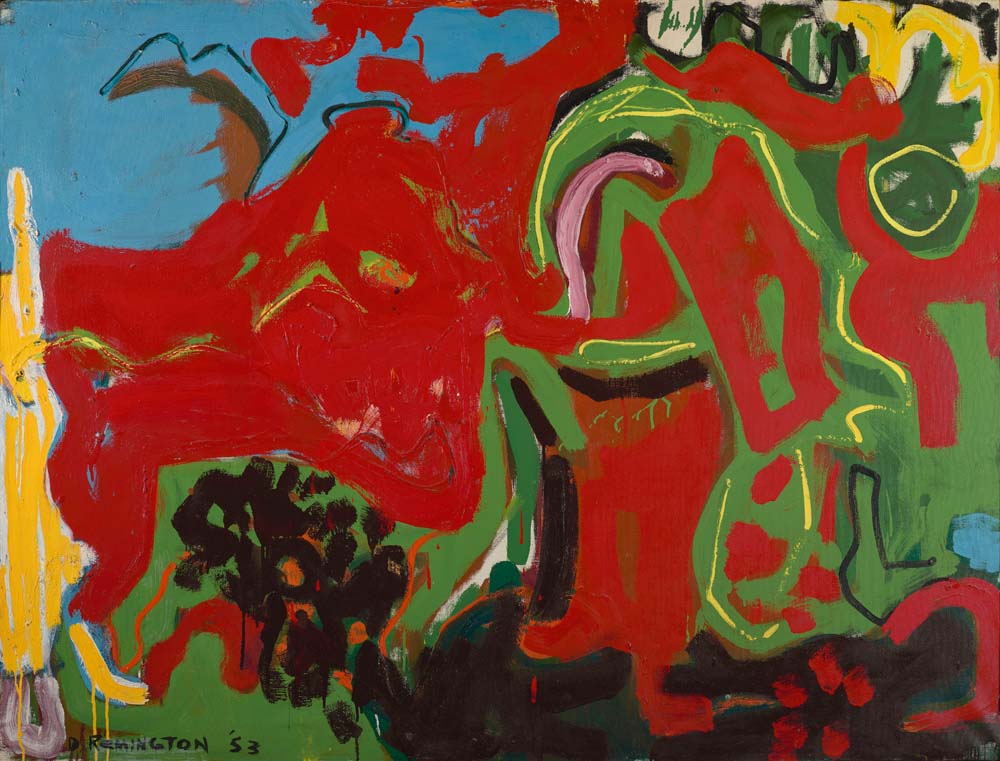

Premiering in Denver, Women of Abstract Expressionism is the first full-scale museum presentation of the work of the women involved in this important art movement. Twelve artists from both the East and West Coasts are represented, including Jay DeFeo, Helen Frankenthaler, Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, and Deborah Remington. Fifty-one paintings, many large-scale, command the entire fourth floor of the museum (plus a smaller adjunct show one floor down).

Often referred to as the first fully American modern art movement, Abstract Expressionism began in the 1940s in New York City, stealing the art world spotlight away from Paris. The founding group, sometimes referred to as the “New York School,” was stylistically diverse and included such well-known artists as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, and Clyfford Still. By comparison, even the most intrinsic women in the group, such as Lee Krasner, have received little attention. Chanzit did not set out to do a show specifically about women, but she immediately recognized the quality of the work and felt it deserved a much larger audience. “These are important paintings by exceptional artists,” she emphasized, adding that the vagaries of history and gender roles helped to keep them largely invisible.

Often referred to as the first fully American modern art movement, Abstract Expressionism began in the 1940s in New York City, stealing the art world spotlight away from Paris. The founding group, sometimes referred to as the “New York School,” was stylistically diverse and included such well-known artists as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, and Clyfford Still. By comparison, even the most intrinsic women in the group, such as Lee Krasner, have received little attention. Chanzit did not set out to do a show specifically about women, but she immediately recognized the quality of the work and felt it deserved a much larger audience. “These are important paintings by exceptional artists,” she emphasized, adding that the vagaries of history and gender roles helped to keep them largely invisible.

All the women included are noteworthy; several were highly influential. One such artist was New Yorker Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011), whose “soak-stain” technique launched the transition from Abstract Expressionism to what critic Clement Greenberg recognized as “the next big thing”: Color Field painting. First employed in her 1952 Mountains and Sea, Frankenthaler’s process involved pouring thinned paint (initially turpentine-thinned oil paint, then later, water-thinned acrylic) onto raw canvas to create washes of color that completely ignored not only representation, but dimensionality.

All the women included are noteworthy; several were highly influential. One such artist was New Yorker Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011), whose “soak-stain” technique launched the transition from Abstract Expressionism to what critic Clement Greenberg recognized as “the next big thing”: Color Field painting. First employed in her 1952 Mountains and Sea, Frankenthaler’s process involved pouring thinned paint (initially turpentine-thinned oil paint, then later, water-thinned acrylic) onto raw canvas to create washes of color that completely ignored not only representation, but dimensionality.

A prolific artist and tireless experimenter, Frankenthaler had a long career that began in 1950, with her inclusion in a major exhibition curated by Adolph Gottlieb. The very next year, New York’s Tibor de Nagy Gallery hosted her first solo show, and she was included in the 9th Street Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture. It was in this landmark show that Greenberg recognized her talent and ignited her career. By 1959, Frankenthaler was regularly included in international shows, and in 1960 had her first museum solo show, at the Jewish Museum in New York. Over the next 50 years, Frankenthaler continued to create and exhibit significant work in a variety of mediums, including ceramics, sculpture, tapestry, and printmaking, in addition to painting. She continues to be the subject of museum exhibitions around the world, including at the Whitney Museum, Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) New York, and the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh.

A prolific artist and tireless experimenter, Frankenthaler had a long career that began in 1950, with her inclusion in a major exhibition curated by Adolph Gottlieb. The very next year, New York’s Tibor de Nagy Gallery hosted her first solo show, and she was included in the 9th Street Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture. It was in this landmark show that Greenberg recognized her talent and ignited her career. By 1959, Frankenthaler was regularly included in international shows, and in 1960 had her first museum solo show, at the Jewish Museum in New York. Over the next 50 years, Frankenthaler continued to create and exhibit significant work in a variety of mediums, including ceramics, sculpture, tapestry, and printmaking, in addition to painting. She continues to be the subject of museum exhibitions around the world, including at the Whitney Museum, Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) New York, and the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh.

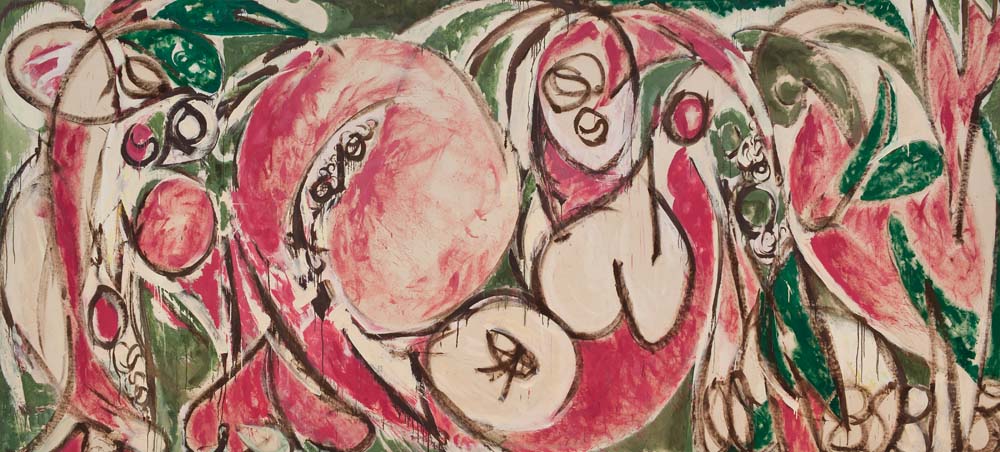

Among the West Coast artists featured in Women of Abstract Expressionism, Jay DeFeo (1929-1989) played an equally pivotal role. She grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area and after graduating from the University of California Berkeley in 1951, lived in Europe and North Africa for 18 months on a fellowship. There, DeFeo created her first major body of work, her own unique fusion of Abstract Expressionism with aspects of Italian architecture, as well as Asian, African, and prehistoric art.

Among the West Coast artists featured in Women of Abstract Expressionism, Jay DeFeo (1929-1989) played an equally pivotal role. She grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area and after graduating from the University of California Berkeley in 1951, lived in Europe and North Africa for 18 months on a fellowship. There, DeFeo created her first major body of work, her own unique fusion of Abstract Expressionism with aspects of Italian architecture, as well as Asian, African, and prehistoric art.

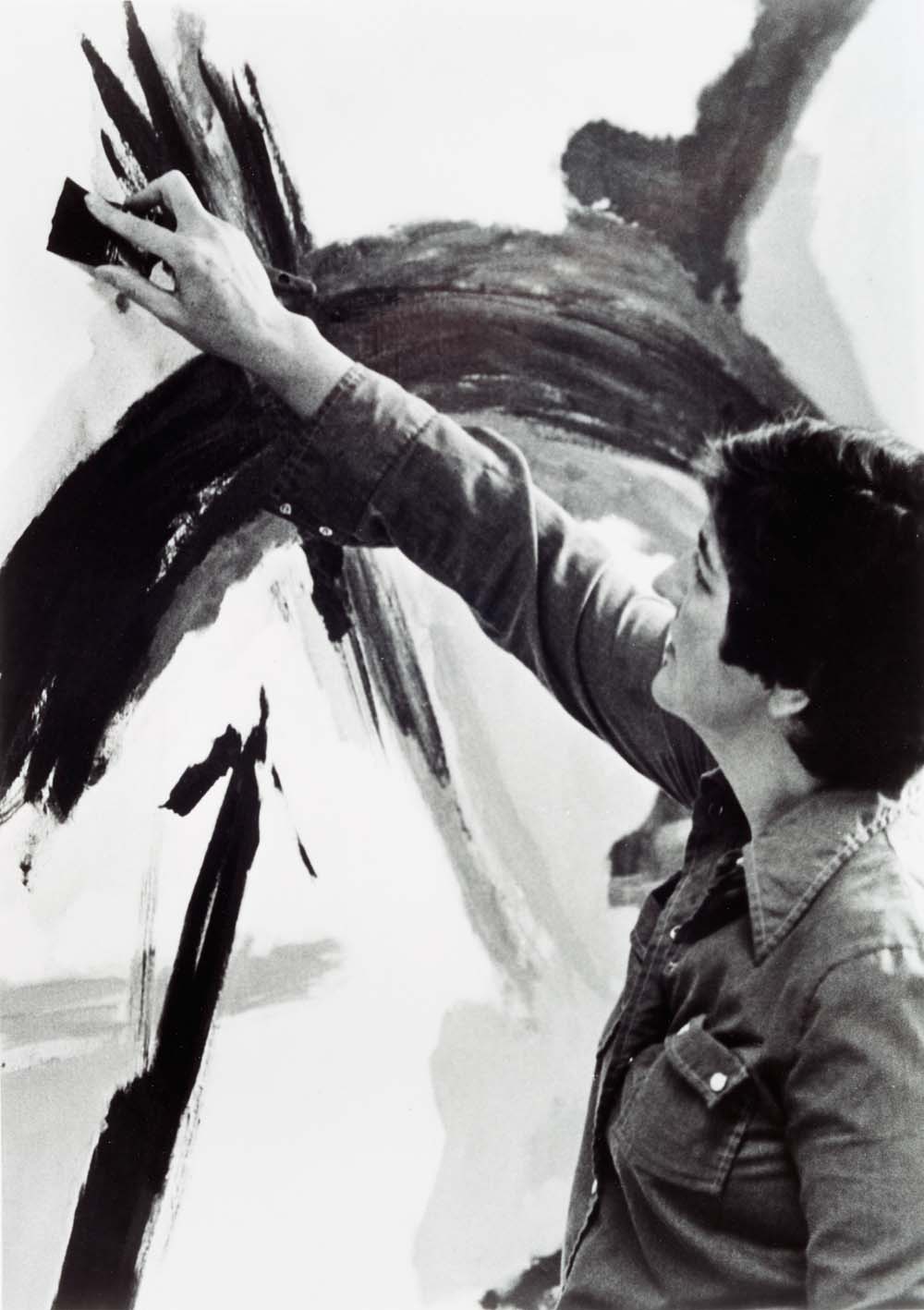

In 1959, DeFeo’s career experienced two major milestones: a solo show at Dilexi Gallery in San Francisco, and inclusion of her work, alongside artists such as Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella in the groundbreaking show Sixteen Americans at MOMA New York. After a solo show in 1960, in L.A., DeFeo focused for the next eight years on the evolution of a single, momentous work titled The Rose. Her most famous piece, it incorporates thick layers of oil paint, which she chiseled away to create what she called “a marriage between painting and sculpture.” More than 10-and-a-half-feet tall and weighing one ton, it incorporated wooden dowels to support the paint and required a forklift to move. After first being exhibited in 1969, The Rose was covered and stored behind the wall of a conference room until 1995, when a curator had it excavated and restored. Until her death at age 60 in 1989, DeFeo continued to create and exhibit unique pieces that mixed media and techniques to blur the boundaries between painting, sculpture, drawing, and collage. Chanzit is quick to point out that all the women were as bold in their art-making as the men, experimenting with technique, subject matter, and materials. To combat the notion that female artists were just “followers,” she selected earlier work, painted in the late 1940s and 1950s. “I wanted to show that these women were creating work right alongside the men.”

In 1959, DeFeo’s career experienced two major milestones: a solo show at Dilexi Gallery in San Francisco, and inclusion of her work, alongside artists such as Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella in the groundbreaking show Sixteen Americans at MOMA New York. After a solo show in 1960, in L.A., DeFeo focused for the next eight years on the evolution of a single, momentous work titled The Rose. Her most famous piece, it incorporates thick layers of oil paint, which she chiseled away to create what she called “a marriage between painting and sculpture.” More than 10-and-a-half-feet tall and weighing one ton, it incorporated wooden dowels to support the paint and required a forklift to move. After first being exhibited in 1969, The Rose was covered and stored behind the wall of a conference room until 1995, when a curator had it excavated and restored. Until her death at age 60 in 1989, DeFeo continued to create and exhibit unique pieces that mixed media and techniques to blur the boundaries between painting, sculpture, drawing, and collage. Chanzit is quick to point out that all the women were as bold in their art-making as the men, experimenting with technique, subject matter, and materials. To combat the notion that female artists were just “followers,” she selected earlier work, painted in the late 1940s and 1950s. “I wanted to show that these women were creating work right alongside the men.”

The seeds for Women of Abstract Expressionism were sown in 2008 in New York City. Chanzit “taking in a gazillion shows in two, three days,” including an abstract expressionist exhibit centered on Clement Greenberg and his fellow critic Harold Rosenberg. It featured several artists, including men of color and women, that she wasn’t familiar with—even though many of them had studied with influential artists like Still or Hans Hoffman, and exhibited at important venues (including The Six Gallery in San Francisco, co-founded by Remington and site of the first public reading of Alan Ginsberg’s Howl). She was inspired to bring a cohesive show of these women’s powerful work, not to mention their stories, to a new audience. “No matter how much someone knows about art history, I probably have an artist or two that will surprise them,” she said. Chanzit limited the number of artists shown in the gallery to 12 (the catalogue includes more than 50) and the number of paintings to 51 so that each artist has her own space. “This individuality is something very special about the work. These paintings are very personal reactions to seasons, people, time of day, an experience in a chapel or at a bullfight,” she said and notes that very few of the pieces are untitled, an indicator that each is tied to a personal experience.

The seeds for Women of Abstract Expressionism were sown in 2008 in New York City. Chanzit “taking in a gazillion shows in two, three days,” including an abstract expressionist exhibit centered on Clement Greenberg and his fellow critic Harold Rosenberg. It featured several artists, including men of color and women, that she wasn’t familiar with—even though many of them had studied with influential artists like Still or Hans Hoffman, and exhibited at important venues (including The Six Gallery in San Francisco, co-founded by Remington and site of the first public reading of Alan Ginsberg’s Howl). She was inspired to bring a cohesive show of these women’s powerful work, not to mention their stories, to a new audience. “No matter how much someone knows about art history, I probably have an artist or two that will surprise them,” she said. Chanzit limited the number of artists shown in the gallery to 12 (the catalogue includes more than 50) and the number of paintings to 51 so that each artist has her own space. “This individuality is something very special about the work. These paintings are very personal reactions to seasons, people, time of day, an experience in a chapel or at a bullfight,” she said and notes that very few of the pieces are untitled, an indicator that each is tied to a personal experience.

Long after the show ends, however, Denver will benefit from several permanent acquisitions made as a result of Chanzit’s efforts. “Once I began my research and discovered these amazing pieces, I wanted people to be able to see some of this work long after the show closed. We have acquired seven pieces so far; some as purchases, some as gifts, by artists in the show or catalogue. DAM will now have a major collection of work by women in Abstract Expressionism.” It was important to Chanzit that the show be included with museum admission. “The experience of being among more than 50 spectacular, large-scale Abstract Expressionist works really is visually extraordinary, and we want it to be a happy surprise for visitors who aren’t expecting it.”

Long after the show ends, however, Denver will benefit from several permanent acquisitions made as a result of Chanzit’s efforts. “Once I began my research and discovered these amazing pieces, I wanted people to be able to see some of this work long after the show closed. We have acquired seven pieces so far; some as purchases, some as gifts, by artists in the show or catalogue. DAM will now have a major collection of work by women in Abstract Expressionism.” It was important to Chanzit that the show be included with museum admission. “The experience of being among more than 50 spectacular, large-scale Abstract Expressionist works really is visually extraordinary, and we want it to be a happy surprise for visitors who aren’t expecting it.”