AS THE POWER OF PERSONAL COMPUTERS INCREASES, AND ARTISTS LEARN TO MARRY COMPOSITION WITH CODE, A NEW MEDIUM IS MATURING, AND IT’S RAISING PLENTY OF QUESTIONS.

“Boy Meets World” Aluminum Print. 30 x 24 inches. Ed. of 3, 2015 – Milton Melvin Croissant III. “Boy Meets World” is a digital composition by Milton Melvin Croissant III for the RedLine exhibition “Press Play” presented at the McNichols Civic Center in 2015. A Denver native with deep roots in the contemporary and underground art scenes, Croissant is a frequent Denver Digerati collaborator with high-level expertise in digital-motion techniques. Besides his own digital creations, Croissant has produced a wide range of commissioned art-works including stunningly imaginative music videos for musicians around the world.

On September 23, Ivar Zeile is expecting hundreds, if not thousands, of people to gather in front of an enormous LED screen at 14th and Champa, where ads for Comcast, New Belgium and the Denver Zoo generally roll by without too many people taking notice. On that day, on a street corner where the sharp, angled lines of the Denver Convention Center meet the steel waves of the adjacent parking garage, dozens of digital shorts will be projected, free of charge, for anyone who wanders by or plops down a lawn chair to stay a while.

Some of the pieces resemble elaborate screensavers or moments plucked from a video game, while others would be at home in an animated film festival. Some are accompanied by music, narration, and sound effects, others are perfectly silent. Some will make you smile, and some will make you scratch your head. Capturing their similarities would be no easier than quickly comparing Kandinsky, Rothko, Dali, and de Kooning, whose work led to plenty of head scratching in their day.

Despite the comparisons to modern art, strictly speaking, the components of digital art are not all that new. The early days of MTV are filled with 15-second bumpers that featured digital animation and computer-generated music videos like Dire Straits “Money for Nothing.” And though World of Warcraft is a far cry from Space Invaders, old-school arcade games leveraged much of the same technology for entertainment, if not for art. So, what’s different now?

Still from “Escape Pod” – 2015 Jonathan Monaghan. Video (color, sound), media player, screen or projector, 20 min loop. Musice by Furniteur. Courtesy of bitforms gallery, New York. Jonathan Monaghan is a leading new-media artist based in Washington D.C. who works across print, sculpture, and video installation. His meticulously detailed work challenges the boundaries between the real, the imagined, and virtual. Monaghan has been commissioned twice by Denver Digerati starting in 2012, and in 2016 served as one of the first three jurors for Supernova Outdoor Digital Animation Festival. He is represented by bitforms gallery in New York City, and his animations can be collected via Sedition and Daata Editions.

“The internet is a big factor—artists can now put anything they make online, and get an audience,” says Zeile, owner of Plus Gallery and the leader of Denver Digerati, which is championing the art form throughout the city. “A lot of artists are questioning traditional roles of presentation strictly within a gallery environment. They can present their work in many ways on the web and make opportune connections. The other big factor is computer power, which has exploded in the last 10 years. When I started out as a graphic designer, it took 10 hours to create a simple illustration on a Mac. Now artists with entry-level software can do phenomenal things, even create entire worlds in remarkably short time.”

The artists that Zeile represents aren’t kids who play with computers in their parents’ basement—most graduated from art school with degrees in illustration, painting, or sculpture, then adapted their knowledge of lighting, texture, and composition to meet the digital space.

Take Bryan Leister, for example. Long before computers were considered standard equipment in schools, Leister earned his BFA in communication arts. His work for Time magazine, Smithsonian and corporate clients earned him honors from Print and Communication Arts. In 2006, Leister went back to school and earned his MFA in digital fine arts, opening up an entirely new world. He’s now a professor at CU Denver, splitting his time between teaching and producing digital art with an emphasis on interactive exhibits.

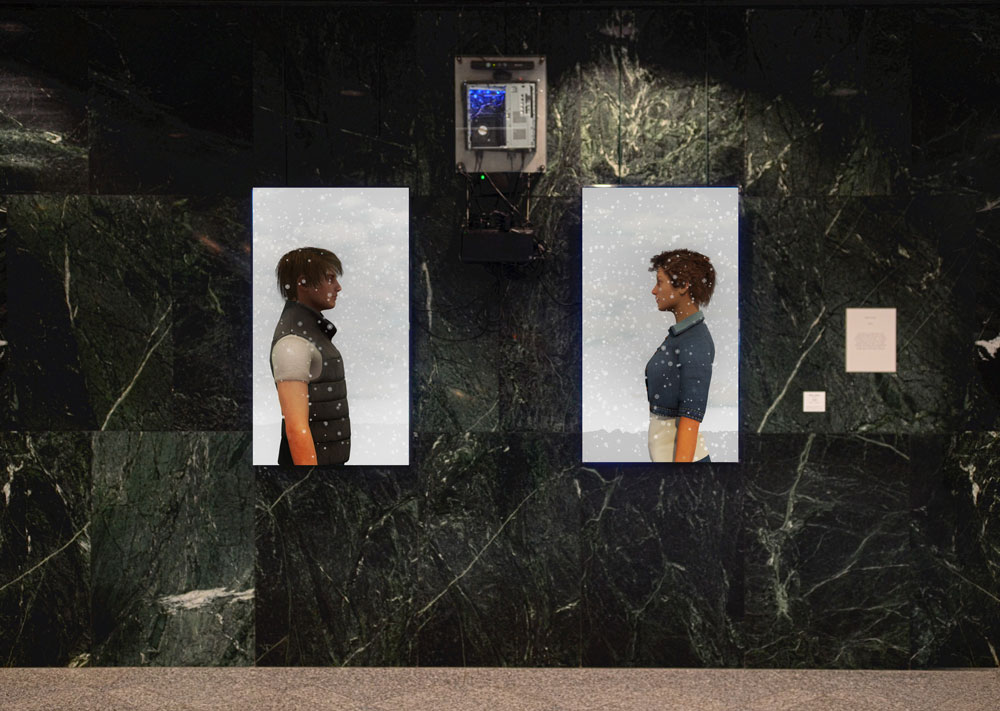

In one exhibit dubbed “Valley Diptych,” Leister projects images of an extremely realistic couple onto a surface. With help from motion-detection cameras and cloud-computing software, their eyes follow visitors as they come and go—a project that asks questions about the role of art and our response to technology.

Like most artists, digital animators often support themselves with full-time or part-time work beyond the studio. Some make video games commercially while others work in advertising. One of Leister’s New York friends recently hired an agent who typically represents musicians and Hollywood actors—recognizing that a wealthy patron who wants a six-screen video installation in her living room may be searching for something closer to performance art than anything framed and hung on a wall.

“Natural Plastic” – 2011 Faiyaz Jafri. Faiyaz Jafri is a skilled animation artist and music composer of Pakistani descent, currently based in New York City. Jafri’s work has been central to Denver Digerati’s focus on digital animation since the inception of Friday Flash in 2011. His most recent animations, including his 2015 Denver Digerati commission “This Ain’t Disneyland,” have screened at countless lm festivals and prestigious forums around the world. Jafri will be one of three jurors for the 2017 Supernova Outdoor Digital Animation Festival held in downtown Denver on September 23.

“The majority of artists in this realm rely on the same sources as any other artists to make a living,” says Zeile. “That can include grant money from major institutions and commissions from major museums. The public is almost always the last to grasp the next big thing, and curators are always the ones who want to say, ‘We came up with this first,’ so they support up-and-comers by funding innovative projects.”

That said, there are, indeed, private collectors of digital art willing to spend as much as $150,000 on digital files and pricy equipment to display it in all its glory. A financial executive in the Hilltop region of Denver, had spent years collecting contemporary Western landscapes by the likes of Jim Colbert, Chuck Forsman, and Ed Burtynsky. But he hadn’t considered digital works until he saw Chiho Aoshima’s piece on exhibit in Houston’s Museum of Fine Art.

“The country was in the midst of the financial crisis, and it felt like being in an airplane where the control panel stops working and everything is upside down,” he says. “A piece about the cycle of life, called ‘City Glow,’ just struck me—like reading a novel or seeing a work of art that changes your life, I just had to see it again.”

If you want to see the Mona Lisa, you can Google it or buy a poster on Art. com to get a close approximation. But digital art is different. “People have taken youTube videos of City Glow, but it’s not the same on a tiny PC or a phone screen,” says the Hilltop collector. “It feels like it’s 1600 again and I’m off to Amsterdam to see a master’s painting.”

“Hyper-Reality” – 2016 Keiichi Matsuda. Keiichi Matsuda is a designer and lm-maker based in London, whose interest is in the dissolving boundaries between virtual and physical. Internationally reknown, Matsuda works with video, architecture and interactive media to propose new perspectives on the city. His 2016 short lm “Hyper-Reality” was awarded Vimeo’s Best Drama of 2016 and has been selected for numerous exhibitions and lm festivals around the world, including Supernova Outdoor Digital Animation Festival 2016’s competition section.

Still from “Disrupter” – 2016 John Butler. John Butler is a computer graphic artist based in the UK. Butler works with 3D animation, motion capture, digital audio and text to speech applications to create Solid State Cinema, a digital moving image form that is native to the web and explores human utility in an age of artificial indifference. Butler was the focus of Supernova’s solo artist spotlight in the inaugural version of the festival in 2016, with an hour-long program featuring seven of his animations from over the last decade.

In fact, he flew to Seattle to another one of the Japanese pop artist’s pieces entitled “Takaamanohara” and ultimately purchased it along with “City Glow,” to be displayed on three giant LED screens in his family room. With his payment, he was given the rights to show the works in his home and even loan them to local museums, just like more traditional forms of art.

For those who can’t afford big-ticket purchases, a handful of websites peddle digital art for the modest collector. Sedition sells pieces for as little as $10, with a platform that hosts purchases in much the same way that Netflix allows you to view films on a few devices whenever you like. Data Editions sells pricier, more contemporary work delivered as discrete digital files, which could simply be copied like an MP3 and sent to anyone—one of the loopholes that comes in the digital world. Electronic Objects sells an actual monitor that displays the pieces you’ve purchased—not all that different from the old Hallmark photo frames that allow you to load JPGs of friends and family members, and display in a constant rotation.

Just as the ownership models for music have evolved over the years, from vinyl to cassette tapes to Napster and iTunes, the ownership model for digital art will continue to evolve. But in a world where younger generations are living untethered lives, sharing workspaces, cars, and so much more, Zeile believes that its portability may ultimately be one of its greatest advantages. Indeed, as screens continue to dominate our lives, and digital projection becomes less and less expensive, there may come a day when artists compete with advertisers for vertical surfaces throughout dozens of major cities. If graffiti artists can transform the RiNo District with paint, why can’t the next generation of artists do the same with pixels?

Denver-based artist and CU professor Bryan Leister works across a broad range of media reflecting his education in design and his career as an illustrator and artist. Leister’s medium of choice is code, ultimately realized through installations, animations, digital images and electro-acoustic audio, video games and digital prints. Leister’s “Strategies” was one of Denver Digerati’s first commissioned works for the new Friday Flash series in 2013. He is represented by Walker Fine Art in Denver.

“Breathe Deep” – 2014 Katie Torn. Katie Torn is one of the leading practitioners of computer-generated contemporary art in the US, holding an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Torn integrates 3D computer graphics and video to model virtually simulated scenes out of the detritus of internet and consumer culture. Following her hugely successful 2014 commission for Denver Digerati “Breathe Deep,” Torn has embedded herself more deeply into Denver’s contemporary art landscape with recent exhibitions at the MCA Denver and the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design. Her animations can be collected via Sedition and Data Editions.

SUPERNOVA: DENVER’S OUTDOOR DIGITAL ANIMATION FESTIVAL, 9-23-17

THE VERY BEST PLACE TO SEE THE SCOPE AND SCALE OF DIGITAL ANIMATION JUST MIGHT BE A 7-HOUR MARATHON DISPLAY THAT’S A FEW FOOTSTEPS FROM DENVER’S MORE WELL-KNOWN PIECE OF PUBLIC ART, LAWRENCE ARGENT’S “BLUE BEAR.”

When the Denver Theatre District was first looking to leverage its LED screens for more than advertising, organizers sought out Ivar Zeile of Plus Gallery, who brought legitimacy to the undertaking. Early on, ads were briefly interrupted by artwork including digital stills and animation, but Zeile soon imagined much more. Rather than sprinkling a few pieces of art between hours of commerce, what if art dominated the screen for the better part of a day? After debuting the concept with “Sightline” in 2012 and offering several “Flash Friday” events in the ensuing years, Zeile partnered with the Theatre District to launch Supernova in September 2016 under the auspices of Denver Digerati.

“We formed the Denver Theatre District to create a sense of light—to give people a feeling of safety, so they’re more likely to gather downtown,” says executive director David Ehrlich. “When we started in 2007, 14th and Champa was a dark little street corner that wasn’t a part of any relevant conversation. Years later, we’re getting emails from artists all over the world, thanking us for putting their work on the screens. It’s really become a great effort in terms of art, but also a great place-making effort.”

The second annual installment of Supernova will take over the Theatre District from 3 p.m. to 10 p.m. on September 23, featuring dozens of digital artists from all over the globe. Programming includes a focus on abstract animation, music videos, student shorts, local artists, gaming art, and a juried competition. Those wishing to go deeper can attend the all-day education forum on September 22. It goes without saying that this is the kind of experience that isn’t artfully conveyed on a piece of paper, so visit supernovadenver.com to learn more.

Sign Up To Hear Ivar Zeile Speak At Denver Design Week 2017!