COLORADO ARCHITECT MIKE PICHE, AIA REIMAGINES A BEACH HOUSE ON KAUAI THAT PAYS HOMAGE TO MID-CENTURY ARCHITECT VLADIMIR OSSIPOFF’S QUEST FOR THOUGHTFUL DESIGN.

Words: Beth R. Mosenthal, AIA Images: Derek Skalko

Located on the South Shore of the Hawaiian Island Kauai, the town of Koloa is as charming as it is eclectic. Originally settled in 1835 (coinciding with the opening of the town’s first sugar mill) Koloa is now a multicultural mix of residents and tourists who enjoy proximity to Poipu Beach. The area is highlighted by lush landscape at every turn, and a laid-back lifestyle rooted in a strong connection to the island’s natural surroundings. When Boulder and Aspen-based architect Mike Piché was asked to help a friend with a beach house in Koloa, he was understandably excited to get started.

A small project latent with possibility, it quickly grew in environmental and architectural ambition. Ultimately, it became a 3,000-square-foot, mechanical-system-free residence for the Bakers–a couple that splits their time between Aspen and Kauai. Complete with a floor plan that encourages seamless indoor/outdoor living and design features that utilize the island’s weather to ensure consistent thermal comfort, the finished residence provides a highly-sophisticated reinterpretation of the term “beach house.”

The house’s L-shaped form creates a dialogue in which the yard becomes an integral, outdoor room for the home. Designed with walls and windows that “disappear” when opened, the architectural elements reinforce the Hawaiian lifestyle in which the lines are consistently blurred between time spent indoors and outdoors.

The site is located in an eclectic neighborhood comprised of homes ranging from plantation-style to sleek and modern. Seeking context and narrative, Piché spent time researching local Hawaiian architectural precedents prior to embarking on the home’s design. He was quickly struck by Vladimir Ossipoff, an acclaimed mid-century modern architect and former American Institute of Architects (AIA) Hawaii president who used his term in office to pursue a highly publicized “war on ugliness.”

Concerned about the rapid commercialization of the Waikiki waterfront in 1964, Ossipoff and his fellow AIA members led a concurrent effort to restrict future development in that area. Ossipoff hoped that by declaring “war” on this specific architectural style, he might raise awareness of the role the people of Hawaii could play in “making Hawaii a more beautiful place to live and work.”

For this project, Piché appreciated Ossipoff’s celebration of many mid-century architectural features, and aimed to retain “the more modern amenities” of Ossipoff’s work. These included strong roof lines, deep overhangs, glass, and the thoughtful use of wood as a warm accent material. In addition, Piché was intrigued that Ossipoff’s homes rarely had air-conditioning, and that he had designed the Baker residence to also be heating and cooling free.

“The design aims to take advantage of the breezes that are pretty much always on the site—the Pacific trade winds that come through,” Piché explains. “We made sure that all of the bedrooms and spaces could open up and flow through. With louvered transoms, open windows, and ceiling fans, a gentle breeze comes through when everything is opened up.”

Additional sustainability features include a PV system that handles the electrical requirements for the home and a solar hot water system that provides heating for the pool and spa.

The floorplan of the home strategically places the primary living spaces including the kitchen, living room and master bedroom on the second floor, maximizing the users exposure to views as well as the surrounding tree canopy. Wood ceilings, floors, and window frames are paired with stark white walls and bold accent colors to juxtapose modern architectural detailing with a sense of warmth and intimacy.

The home’s materials and components were also selected in response to Kauai’s climate and local economy. Working with a highly-skilled Kauai-based builder, Piché sourced materials locally whenever possible. Each of the windows and doors were fabricated by Paradise Millworks, a local shop that helped achieve Piché’s vision of pocket doors and folding windows that “completely disappear” when opened.

For the exterior of the home, Piché was thoughtful in his selection of the finishes. Despite originally having darker colors in mind for the façade, lighter-colored stucco was selected in response to the intense summer heat. Metals were chosen that wouldn’t corrode due to excessive moisture. To underscore the seamless transition from indoor to outdoor living, the entire first floor was covered in a uniform field of highly-durable tile.

After spending a week’s vacation in the finished home, Piché noted that the home “lives much bigger than its 3,000 square feet” due to this blurring of indoor and outdoor spaces.

From the inside of the home, an inverted floor plan places the kitchen, living room, and dining on the upper level. These shared spaces open to strategically curated views of the ocean, mountains, and tree canopy. When outside the home, the main entry provides a special gathering space that doubles as a breezeway.

“When you approach the site, there is one section where you can see the ocean,” Piché explains. “We wanted that to be the view when you walk up to the house, while creating a way for the wind to penetrate the courtyard. This space worked out incredibly well–that little breezeway is one of the main hang-outs with a great view and breeze.”

Thoughtful in its design, execution, and contextual response, it’s safe to assume that Ossipoff would’ve approved of the Baker residence as a present-day interpretation of Hawaiian Modern architecture’s best attributes.

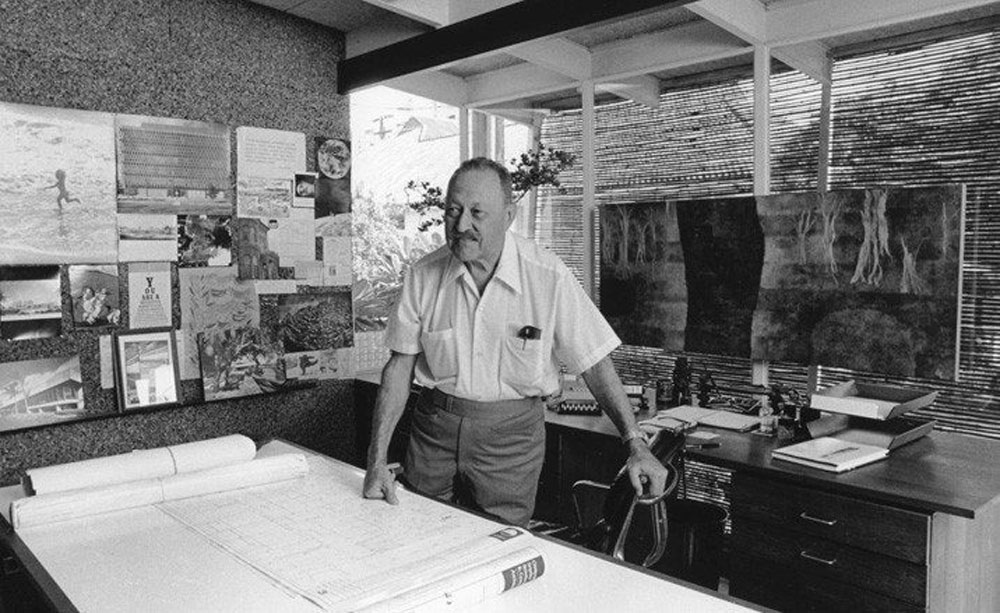

Spotlight: Vladimir Ossipoff, celebrated Hawaiian Architect

Dubbed by many as “the master of Hawaii modern architecture,” Vladimir Ossipoff’s architectural legacy is evident in the proliferation of more than 1,000 homes across Oahu, in addition to well-used commercial and public buildings such as the Honolulu International Airport Terminal and the Thurston Memorial Chapel.

Born in Russia in 1907, Vladimir Ossipoff (1907-1998) grew up in Tokyo, Japan, where his father served as a military attaché for the Russian embassy. Ossipoff immigrated to the United States in 1923, where he attended high school and college in Berkeley. Post-graduation, Ossipoff moved to Honolulu, Hawaii in 1931 in search of work at the onset of the Great Depression.

After working with architect Charles W. Dickey on the Immigration Station at Honolulu Harbor, Ossipoff founded his own architectural practice in his home in 1936. Posthumously described as the “dean of Hawaiian residential architects,” Ossipoff’s translation of Modernist building forms to adapt to Hawaiian living conditions became a defining characteristic of his unique architectural style.

With roots in modernism as well as the influence of his childhood in Japan, Ossipoff’s homes are known for their deep overhangs, strong roof lines, dark woods, native stone and built-in cabinets and fixtures, often constructed by highly-skilled Japanese woodworkers on Oahu. Ahead of his time, Ossipoff often designed huge sliding doors and windows that would open entire walls to the outside to take advantage of natural ventilation.

The Liljestrand House in Honolulu is an ideal example of Ossipoff’s work. Designed for Betty and Howard Liljestrand–a doctor and nurse who had bought the hillside site overlooking Oahu in 1948–and finished in 1952, the home showcases his sophisticated eclecticism.

An architect who was deeply invested in design that responded directly to its context, Ossipoff was vocal in his disdain of generic home and commercial development, believing that ignoring a building’s environment was a hallmark of bad design. While much of Hawaii’s waterfront areas continue to be developed into high-rise condominium towers and suburban housing, Ossipoff’s unique influence and legacy on Hawaiian architecture provides an exceptional counterpoint in his demonstration of timeless, sustainable design.