Denver Art Museum

On View through August 25, 2019

Photography by James Florio

Serious Play presents more than 250 works by such celebrated designers as Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard, and Eva Zeisel, in addition to many lesser-known designers, including Ruth Adler Schnee, Henry P. Glass, and Paul Rand. Rejecting uniformity, these designers embraced the newfound freedom of the postwar era to create imaginative home décor, inventive children’s furniture and toys, and corporate identities with a playful spirit. Visitors to the exhibition can appreciate that play, today as in the mid-twentieth century, can be a serious and significant tool to discover new ideas and allow one’s imagination to soar.

After the dreary, monochromatic war years, Americans explored new ways of living within their homes. A renewed appetite for decoration and a psychological need for color flourished. Fanciful home furnishings and vibrant fabrics were favored by the everyday consumer and leading architects alike. Ruth Adler Schnee’s whimsical furnishing and drapery fabrics, inspired by a variety of sources like her garden, abstract art, and even the pins and needles she worked with every day, were typical of the imaginative textile designs that emerged during the postwar era. At the age of 95, Adler-Schne continues to work as a textile designer.

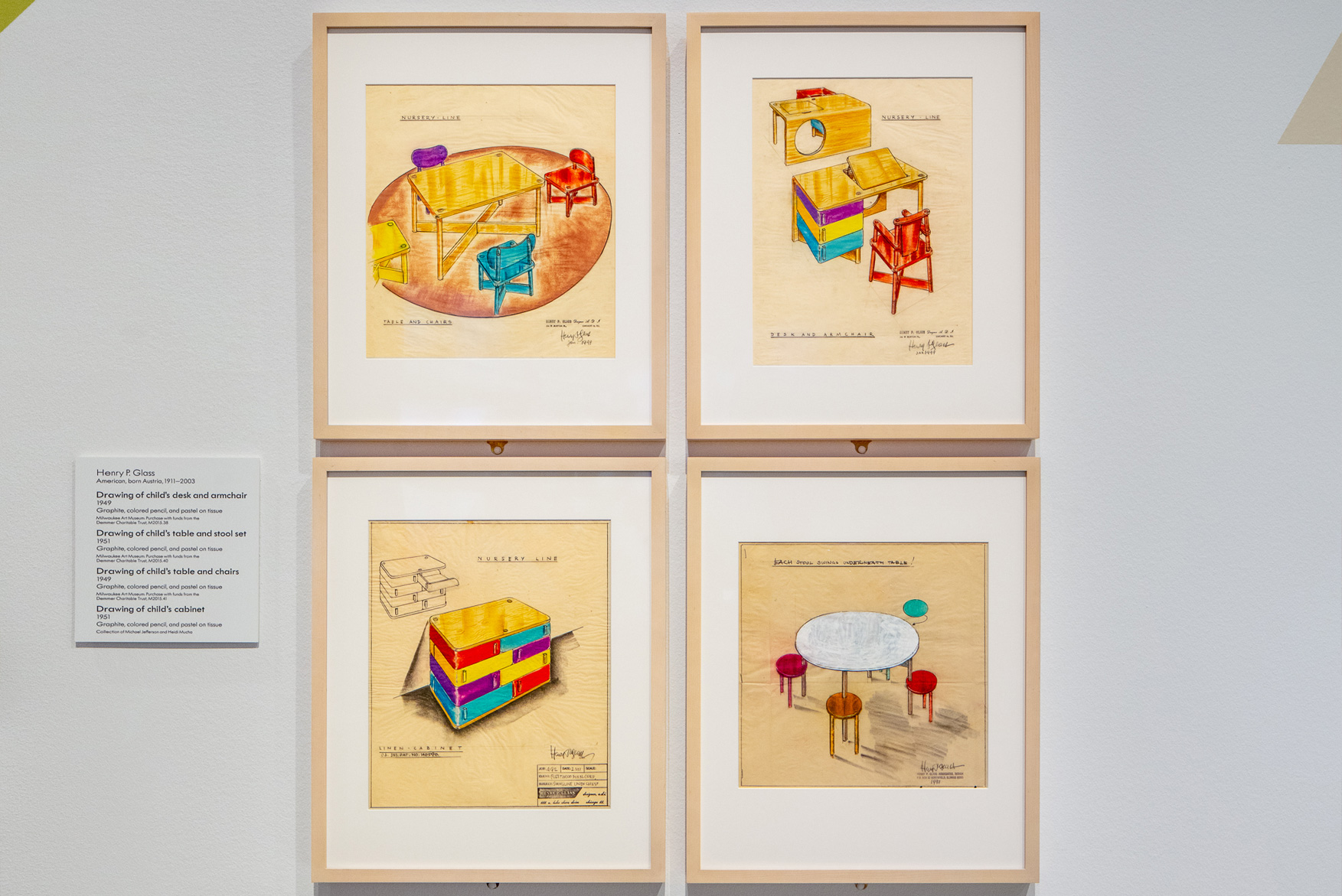

Designing for children was serious business during the postwar era. More choices for furnishings that children could easily manipulate and use without the help of adults became available. Chicago-based designer Henry P. Glass combined functionality with toy-like features in his award-winning Swing-Line series of children’s furniture. Hinged drawers, doors, and stools swing in and out, allowing them to be manipulated without falling apart. When closed, the drawers resemble neat stacks of building blocks. The colors were intended to make it easy for children to keep things tidy by coding which drawer was for what things.

In 1961, Herman Miller opened Textiles & Objects, an experimental retail venture in New York City. Conceived of and designed by Alexander Girard, the showroom sold his colorful textiles and furniture by other prominent designers of the time, including the Eameses and Nelson, alongside folk art and other handcrafted objects. The global folk art ranged from Mexican ceramic figures to Indian bronzes, all of which were selected by Girard and his wife, Susan, during their extensive travels. Although the shop was open for only a few years, it is remembered today for its unique expression of Girard’s personal and professional passions.

Play was not restricted to domestic and children’s settings. Graphic designers, such as Paul Rand, created images that playfully jumped off the page and into the hearts and minds of the American public in imaginative advertisements and packaging designs for corporations. Rand reimagined El Producto’s cigar—in the form of clowns and kings to laborers and gentlemen—as part of an ongoing series for the company. By giving the inanimate product a distinct personality, Rand reinforced his argument that play is not just for children. “Without play, there would be no Picasso,” according to Rand. “Without play, there is no experimentation. Experimentation is the quest for answers.

Throughout the exhibition, visitors of all ages are invited to explore how play can drive their own creativity. Opportunities for play abound in the exhibition, including moments to spin toy tops, build with the Charles and Ray Eames’s House of Cards, arrange a midcentury-inspired room on a digital table, and compose with the classic Colorforms toy. In the Free Play Zone, visitors can try on whimsical masks and bring them to life in a colorful theater, climb on or under Isamu Noguchi’s play sculpture, and creatively combine the components of Ann Tyng’s Tyng Toy. There are also delightful videos by Charles and Ray Eames to enjoy throughout the exhibition, including Tops, Parade, and Toccata for Toy Trains.