POWER, SYMBOLISM AND MODERN DESIGN LAUNCH AN INNOVATIVE NEW BUILDING ON THE HISTORIC U.S. AIR FORCE ACADEMY CAMPUS.

WORDS: Charlie Keaton | IMAGES: David Lauer

During the course of a cadet’s four years at the United States Air Force Academy, he or she experiences roughly 160 hours of applied character and leadership training. In years past, that work took place in as many as 10 different venues, including off-site locations in downtown Colorado Springs. Bringing it all under one roof required volumes of practical functionality. For design firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, creating something aesthetically beautiful without compromising the surrounding environment required a thorough understanding of virtually all aspects of academy life—not to mention a meticulous and artful attention to detail. Up, up, and away.

Tucked away in the rolling foothills of northwest Colorado Springs sits a breathtaking new building on one of the nation’s most architecturally significant campuses. Because of its remote location, and because it doubles as a military installation, most locals will never see it. Many know nothing of it at all. But the Center for Character and Leadership Development (CCLD) at the United States Air Force Academy, unveiled in April, is that rare project with a level of design innovation that lives up to the site’s rich legacy. Fully appreciating the significance of the CCLD, however, requires context. The Academy itself sprang to life in the 1950’s and even then, the Air Force never lacked ambition. Charles Lindbergh was commissioned to fly airplanes into each of the three finalist sites and provide feedback about location, flying conditions, and environmental fit. Cecil B. DeMille designed the uniforms. Dan Kiley handled landscape architecture. Ansel Adams took the photographs. And the design review board boasted a who’s-who of industry icons, including Eero Saarinen, Wallace Harrison, Welton Becket, Pietro Belluschi, and, unofficially. Walt Disney, who had recent experience transforming a massive tract of land into his own majestic, self contained world.

The Chicago-based office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM)-and architect Walter Netsch in particular-were tasked with converting 18,500 acres of raw ranch land into a fully functioning service academy with 170 miles of roads and 600 miles of utilities. What’s more, the timeline was unforgiving. The initial go-ahead came when President Eisenhower signed Public Law 325 in the spring of 1954, authorizing the Academy’s establishment, Design and construction had to be sufficiently complete to accommodate the fist class of cadets in 1958.

That deadline, which seemed so daunting at the time, turned out to be the catalyst for some truly historic design. In the name of simplification, Netsch came up with a streamlined module: The Academy would be designed around a seven-foot grid. He based his decision on the realization that the most repetitive features on campus would be cadet dorm rooms, and that American beds are approximately seven feet long. It was a modest starting point with grand implications.

“For the entire cadet area, Walter laid out a seven-foot grid,” said Duane Boyle, Deputy Director of Installations and Campus Architect for the Academy. “And out of that came all the buildings, the tree locations, everything. Seven divides in half to three-foot-six-inches, which is the joint spacing on the granite walls. That divides in half again to one-foot-nine-inches, which is the size of the marble pavers. Multiples of seven feet get us to the column base spacing, and the spaces between the buildings. Even the chapel spires are on 14-foot center.”

This concept, born of time constraints, helped orient what quickly became an iconic example of International style architecture. Everything on the sprawling campus feels properly proportioned and scaled for human use. So when the time came to add a new building—and not just any building, but a permanent home for one of the Academy’s most intrinsic programs—Netsch’s vision informed the design guidelines. Once again, SOM, whose relationship with the Academy now stretched back nearly six decades, was tapped to handle design. But rather than follow the path of least resistance, the Academy conjured a design competition between the Chicago, New York, and San Francisco offices. New York prevailed, based partially on, as Boyle describes it, “the power and the symbolism of the design.”

INTO THE CLOUDS

From the outside, the CCLD’s 105- foot glass tower looks like a vertical stabilizer (more commonly known as the tail of an airplane). Its lean is the precise latitude of Colorado Springs, bringing the height of the tower halfway between that of nearby Arnold Hall and the top of the chapel spires. The aggressive use of glass—966 panes in all— creates a striking visual, but also presented some serious design challenges, not the least of which was solar orientation. The broadest lean side faces due south, which is high sun. The other prominent sides face east and west, which are low- angle sun. “We didn’t want people inside roasting under extreme sunlight,” said Roger Duffy, Design Partner at SOM. “But we didn’t want to muck up the inside with blinds because it would alter the character of the whole thing.”

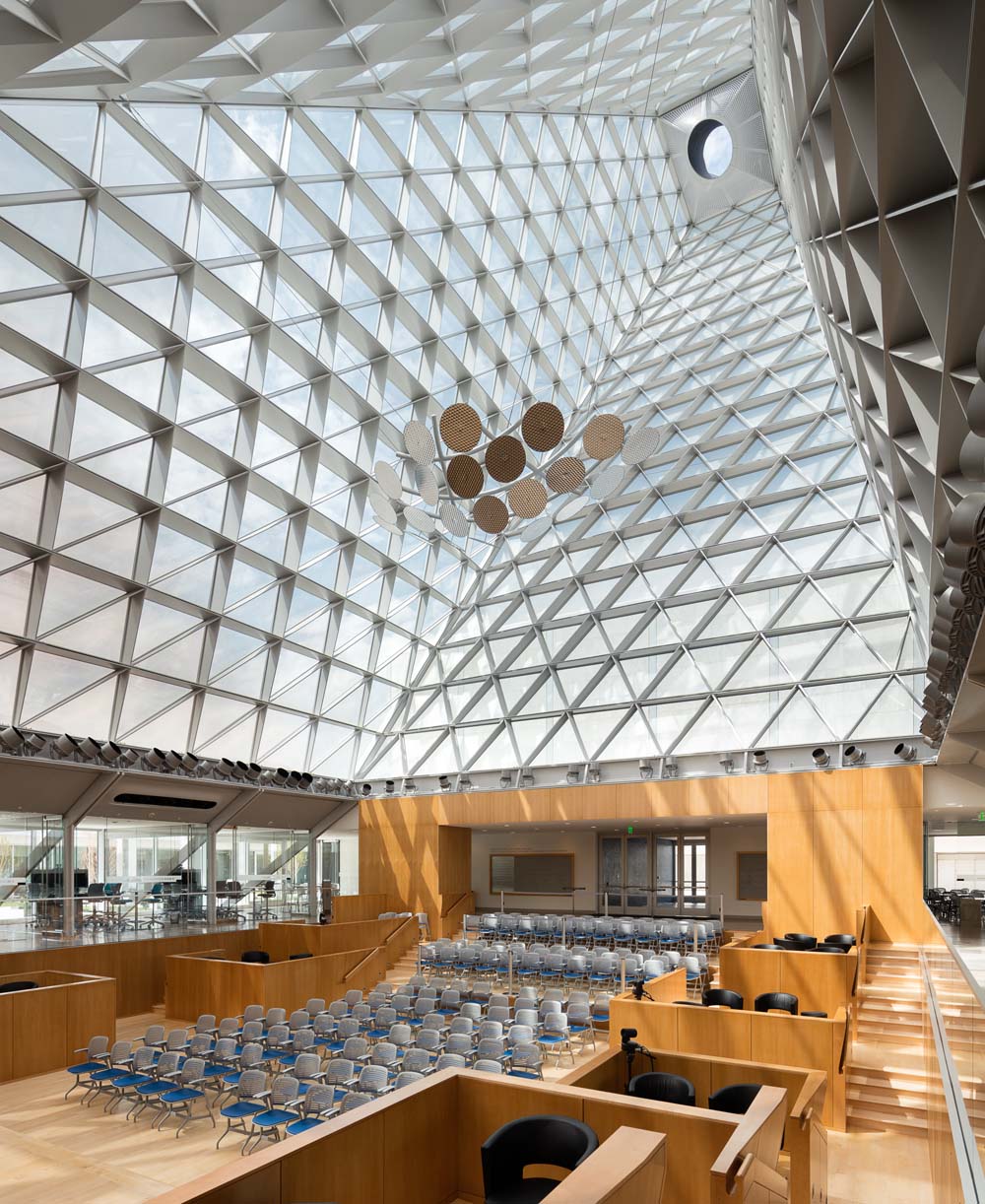

With that in mind, SOM struck on the idea of embedding ceramic frit in the surface of the glass to create a gradient effect. As the sun moves through the sky, the main hall interior is shielded from excessive glare or heat while still admitting loads of daylight. The trusses bow subtly into the space on all four sides, which began as a structural necessity but which also buffers the amount of light that shines down on the floor below. Cadets love that the effect resembles a jet ascending through the clouds.

Beneath the upward reach of the glass tower sits a main hall with the flexibility (and appeal) to host everything from a guest appearance by Vice President Joe Biden to a causal breakout session between classmates or faculty. A bevy of large theatrical lights rings the presentation space, pointing discreetly toward an array of suspended mirrors resembling a sculpture. “The last thing we wanted was to hang all kinds of technical-looking lights to shine on speakers or events,” said Duffy. “So we came up with the idea to embed all the lights within the structure and then use the mirrors to precisely reflect the lights onto appropriate parts of the space.”

This approach had the added benefit of giving the room what Duffy calls a “dual life”—by day the building is sleek and minimally transparent, but by night it draws the eyes inward and reveals the physicality of the space. Along the perimeter of the main hall is a series of collaboration rooms, each interconnected and filled with cutting edge technology. And atop the tower is an oculus that points directly at Polaris, the North Star, which has been a powerful symbol for the Air Force since its inception. No matter how the earth rotates, Polaris will be visible through the oculus for thousands of years, reminding cadets to fly right (literally and figuratively), and to make good character and leadership decisions.

The rest of the CCLD snakes in all directions, designed to serve many masters. There are five different entrances for five different constituencies, including everything from cadets and faculty to outside visitors, but from any trajectory the orientation is appropriate and intuitive. At 14 feet below the public plaza, this is essentially a below grade building, but copious windows and modular glass walls pull in a healthy dose of natural light, and more than a little transparency. Clever, meticulous details emerge throughout: glass Murano tile from Italy painstakingly sampled and arranged to match similar features elsewhere on campus; polished concrete poured higher than the finished surface level, so that it could be ground down to resemble the polished terrazzo in other buildings; designer furniture consistent with the original, iconic midcentury pieces that adorned the Academy in the 1950s and 1960s; an inlaid handrail subtly carved into maple walls.

Getting these details just right required strategic vision and willing collaboration—especially considering the constraints imposed by Walter Netsch’s original design philosophy. But constraints can lead to unexpected breakthroughs, too. That was true for SOM in the 1950s, when Netsch’s seven-foot grid produced an International-style campus that continues to draw international acclaim. And it once again proved true during the design and construction of the CCLD.

To illustrate the point, Roger Duffy called on a quote from legendary composer Igor Stravinsky: “The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self of the chains that shackle the spirit…the more art is controlled, limited, worked over, the more it is free.”

In other words, flying right isn’t merely the result of unfettered creativity. Instead, for cadets and architects alike, it’s the product of artful improvisation within thoughtful boundaries. Trust the process, respect the flight plan, and gear up for blue skies ahead.